Demystifying Water for Coffee

Water can be a confusing topic. For example, as I have mentioned in The Professional Barista’s Handbook and Everything But Espresso, “alkalinity” and “alkaline” mean different things. Machine manufacturers focus on avoiding scale, but are generally not aware of what water chemistry is best for flavor, or how to balance the concerns of avoiding scale vs optimizing flavor. Further, the industry’s historical focus on overall TDS has led to a misguided belief that having a reasonable TDS level means water is optimal for coffee making.

I’ll do my best here to simplify the discussion to help cafes, baristas and roasters make decisions about water quality.

The important points to discuss are:

Alkalinity is the single-most important factor in how water will affect coffee flavor.

One must get a laboratory water analysis to know what water-treatment system is appropriate for a cafe or roastery. Test, don’t guess.

Beyond flavor, it is important to ensure your water will not cause scale to precipitate in your coffee machines. This is especially important in high-volume settings such as coffee bars. Sometimes one needs to compromise and allow a little scale or sacrifice a little flavor quality to balance those two concerns.

Some definitions

TDS: Total Dissolved Solids. This means exactly what it says: how much stuff is dissolved in the water. Industry recommendations have historically been to use water with TDS of 100-150, but by itself, TDS is a relatively unimportant number.

Hardness / General Hardness/ Temporary Hardness/ GH: this is the type of hardness created by dissolved calcium, magnesium, and iron cations. GH may influence flavor and scaling risk, but there is little consensus on the optimal level or the ideal balance of Ca+ and Mg+.

pH/ Potential Hydrogen: a measure of acidity, from 1—14. Neutral is 7.0. The pH scale is famously confusing because it is logarithmic. In other words, a pH of 2 is ten times more acidic than a pH of 3. Coffee, having a pH around 5, is not all that acidic, despite its reputation. For reference, lemon juice (pH of 2) is 1000 times more acidic, and stomach acid can be far more acidic than lemon juice. Water pH is not particularly important when considering water for coffee because the alkalinity level will have a far greater impact on final acidity in the cup.

Alkaline: this simply means pH is above 7, or the water is “basic” and not acidic.

Alkalinity/ Bicarbonate/ Buffer/ Carbonate Hardness/ KH: As you can see by these terms, whoever created water-chemistry nomenclature was a misanthrope. Alkalinity is a solution’s resistance to becoming more acidic upon the addition of an acid. Alkalinity is — by far — the single most important factor in how water chemistry will affect coffee flavor. Simply put, higher alkalinity makes coffee less acidic. Lower alkalinity makes coffee more acidic. These statements are true regardless of the water pH.

My personal preference for lightly roasted, well-developed beans is an alkalinity level of 30—40ppm. Your preferences may differ, and there may be times you intentionally choose unusual alkalinity levels to enhance or tone down acidity, depending on the bean and roast quality and degree. For example, you may choose low-alkalinity water to enhance the acidity of a flat-tasting coffee, etc.

Please note that water can have high alkalinity (buffer) but not be alkaline. As I wrote in the The Professional Barista’s Handbook (2008):

A solution can be very alkaline but have low alkalinity, and vice versa. As an analogy, think of alkaline as the solution’s location on the political spectrum. Let’s say alkaline refers to being on the right, and acid refers to the left; alkaline denotes being conservative, acid denotes liberal. (No political commentary intended!) Alkalinity, on the other hand, is analogous to stubbornness, or resistance, to becoming more liberal. Of course, one can be at either end of the spectrum (acid or alkaline) and still be resistant (have high alkalinity) or amenable (low alkalinity) to becoming more liberal.

Water for coffee at home

If you make coffee at home, there are a few convenient options:

Search online for your city’s municipal water-quality report. It may help you know if your tap-water alkalinity level is high or low, or if your water contains contaminants you want to avoid, and may only be removed via reverse osmosis. Knowing your tap-water chemistry will help you make an informed decision about how to optimize it for coffee brewing.

Bottled water: I’ve never been somewhere in the world that didn’t offer at least one bottled-water option that was pretty good for coffee brewing. It’s worth reading labels and looking online to learn more about the bottled-water options in your area. If you can’t find a single bottled water with your preferred alkalinity level, consider blending distilled water with other bottled water to achieve your target alkalinity.

Buy demineralized or distilled water, and add dry salts or a product like Lotus Water Drops. This can be a great way to learn the effects of different water chemistry on coffee flavor, and help you dial in your preferences. Many grocery stores sell affordable reverse-osmosis water that you can buy and pour into large, reusable jugs.

If your tap water is naturally good for coffee, you may want to use a simple carbon filter such as a Brita pitcher or similar. If your water is hard and/or has very high alkalinity, you may want to try the Peak Water pitcher or a similar product.

Water for coffee in a commercial setting

If you survey machine manufacturers, they will rightly steer you toward water treatment that will protect your machines from scale (the precipitation of CaCO3). However, most machine providers or servicers are not aware of what water chemistry makes coffee taste best.

A simple way to estimate the scaling potential of water at various temperatures is to use an online Langelier Saturation Index calculator. I have mentioned the LSI in several of my books:

For many years, I battled with my espresso-machine supplier because he insisted that i use a water softener to protect the machine. I argued that I did not need a softener, since my water would not produce scale in the machine, and that further, softening very hard water damages coffee flavor, so a softener is never the best solution. He finally relented when I showed him the LSI.

In more recent years, the industry has avoided the risks of water softeners by favoring reverse-osmosis systems with blending valves. These systems remove approximately 90% of the dissolved solids from water by reverse osmosis, and offer the option of blending the RO water with carbon-filtered tap water.

Let me offer an example of how to use an RO system with blending valve. Let’s say your tap water has:

80 TDS

60 GH

60 KH

but you prefer alkalinity (KH) of 30.

The RO water will have KH of 6 (we will assume it removes 90% of dissolved solids in the water). The “blending water” that passed only through a carbon filter will have KH of 60.

If you use 55% RO + 45% blending water, the result will be:

.55*6 + .45*60 = 3.3 + 27 = 30.3 KH

Please note that while RO systems are common in cafes, they are inappropriate in places with soft tap water. For example, a cafe in Manhattan may have 25 TDS and 15 KH. Removing any minerals from that water would be a mistake, and the cafe should only use a sediment filter + carbon filter to remove undesired tastes and odors.

Test, don’t guess

I always ask my clients to get a water test from a laboratory before choosing a water system. I have my preferred labs, and I would personally pay the $100-$200 for a test rather than get a free test from a water-treatment company, partly to not feel in debt to that company, and partly to get a comprehensive test that few, if any, water-treatment system companies provide for free

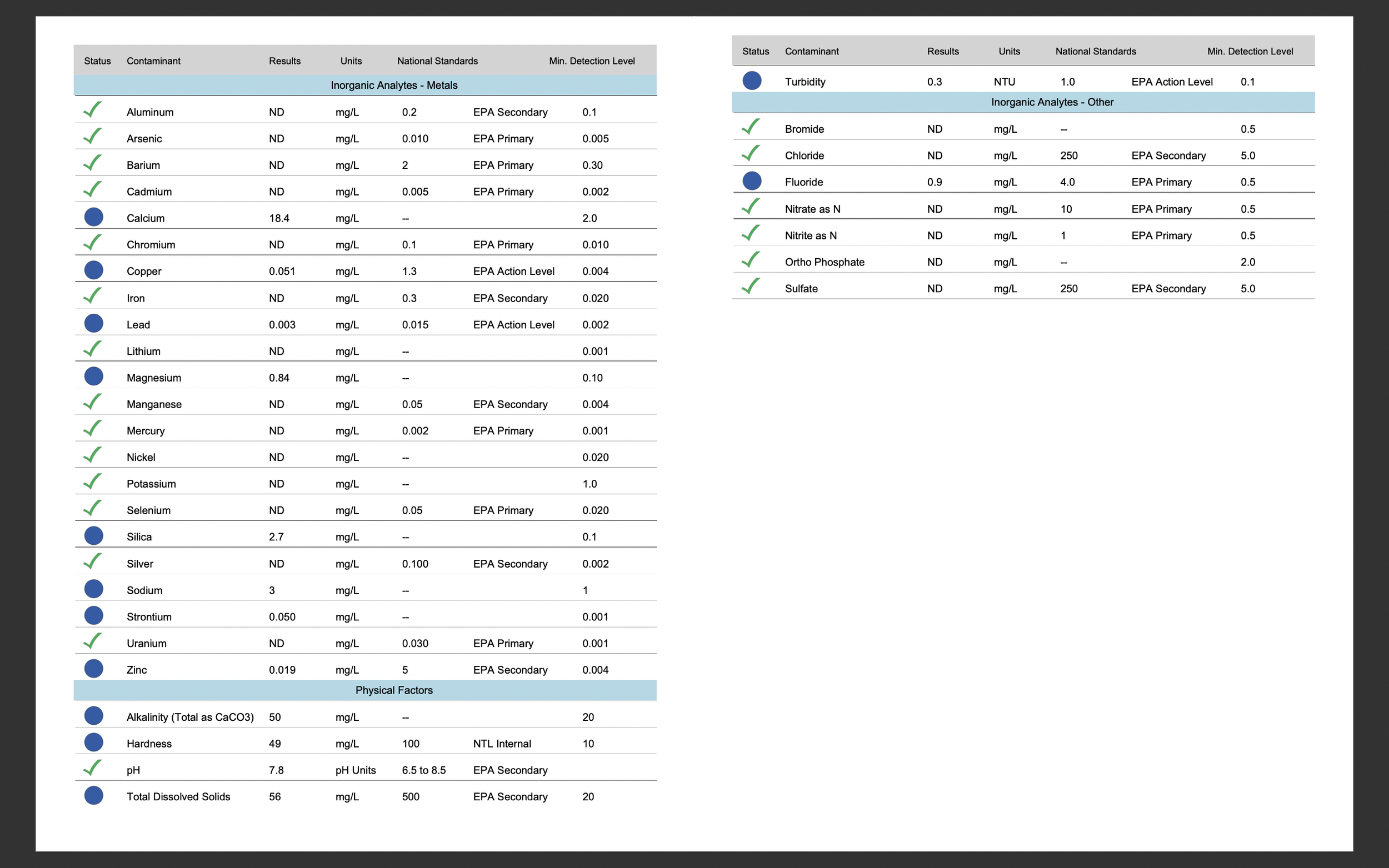

For example, below are the test results of the water at the Prodigal roastery. As you can see, the alkalinity is slightly above my preferred range, but close enough to that range that I don’t think it’s worth getting an RO system. We are satisfied with the coffee flavor after passing this water simply through a sediment filter and carbon filter.